With today's technology, would it be possible to launch an unmanned mission to retrieve Voyager I?

—Elliott Bennett

Voyager I is farther from Earth than any other manmade object. After getting a pair of gravitational kicks from Jupiter and Saturn, it’s headed out of the Solar System at a pretty high speed, and nothing else we’ve built is on track to pass it.

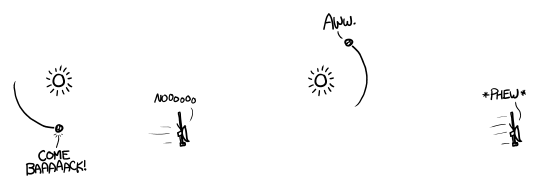

Strangely, as of the day I’m writing this, Voyager is actually getting closer to us, because Earth is in a part of its orbit where it’s approaching Voyager faster than Voyager is fleeing. But in a few months, we’ll swing around the Sun and Voyager will again be getting farther away.

It has a 35-year head start, so it would be hard to catch. But catching up isn’t the problem.

New Horizons, the spacecraft currently headed out of the Solar System by way of Pluto, is never going to catch up to Voyager—it’s not moving fast enough and it’s headed in the wrong direction. But it could have.

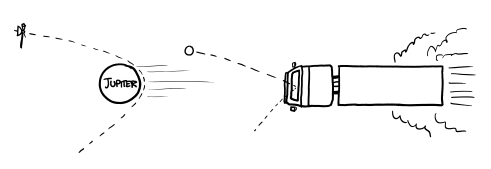

The reason Voyager is moving so fast is that it got gravitational assists from Jupiter and Saturn, while New Horizons only got one from Jupiter.

Gravity assists aren’t paradoxical magic. It’s just like bouncing a tennis ball off a passing truck. Gyroscopes, on the other hand, ARE magic.

If New Horizons had ditched the Pluto objective and waited for the right planetary alignment (the 2030s look promising), it could have swung by Jupiter and Saturn, then caught up to Voyager in as little as a century or two! (Assuming we could manage to hit Voyager from that far away. But I bet we could; our rocket scientists are pretty good at rocket science.)

Of course, getting there’s the easy part. The hard part is getting back.

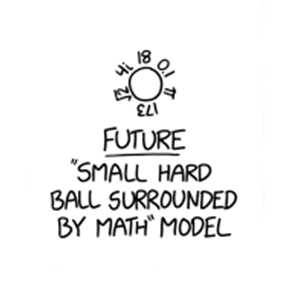

Voyager weighs a little less than a ton and is moving away at 17 kilometers per second (if it were in the atmosphere, that would be Mach 50). And since it’s out in interstellar space, there are no speeding Jupiters to grab on to. Stopping Voyager is going to take a lot of fuel.

It’s what engineers call the tyranny of the rocket equation: As the amount that you want to change your speed (“delta-v”) goes up, the fuel required increases exponentially. The equation tells us that to turn the 720-kilogram Voyager around, we’re going to need at least 30 tons of fuel.

But to get that fuel out there, we need even more fuel. And to get that fuel, we need even more fuel. (This is where the tyrannical rocket equation gets its exponential term.) In fact, to rescue Voyager, we’d have to launch a fleet of—at minimum—60 New Horizons-sized spacecraft loaded with nothing but fuel.

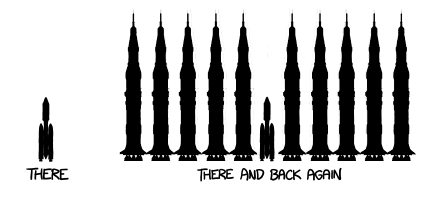

Could we do it? Sure. There are a couple plausible ways. Instead of building five to ten dozen fuel-laden Titan IIIEs, we could just build a fleet of ten or fifteen Saturn Vs, and do the whole thing with fewer launches. But however we did it, it would be a massive and expensive operation similar in scale to the Apollo program.

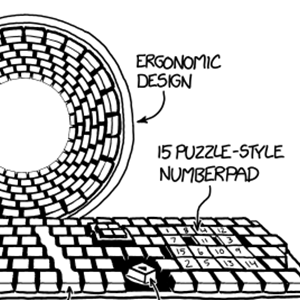

The difference between the launch vehicle we’d used to get Voyager out of the Solar System and the fleet we’d need for a round trip is striking:

Fortunately, there’s one way around the tyranny of the rocket equation: Ditch the rockets.

Ion engines—which use electric fields to accelerate exhaust gas to high speeds—are far more efficient than chemical rockets, and they make accelerating to high speeds much more plausible.

The reason we’re not using them for everything is that they produce very little thrust, so it takes a long time to get up to speed. It’s like if you had a car that gets amazing mileage but has a one-horsepower engine. (Actually, are you sure that’s not just a horse?) Ion engines are great; the current ones just take forever to get you moving.

But since catching Voyager is going to take a long time anyway, ion engines are fine. We could launch a probe (like this one), send it out to Voyager, latch on, turn everything around, and let it spend a few decades slowing Voyager down.

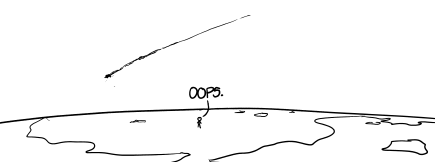

Once Voyager had lost nearly all its speed, the Sun’s gravity would take over, and the probe would begin a long slow slide toward the inner Solar System. This would take about 200 years, and with some extremely careful nudges, we could make sure it falls in an Earth-crossing orbit.

Two centuries later, Voyager would reach Earth and, with no way to slow down, burn up in our atmosphere, because we didn’t think to send out an aerobraking shell with the rescue craft. So that was a waste of a few centuries of work and billions upon billions of dollars.

Maybe a better idea would be to borrow a salvage vessel and set sail for the coast of New South Wales, Australia. There, in the waters off Jervis Bay, the Australian Royal Navy ship Voyager sank in 1964 after an accidental collision.

That one’s probably easier to retrieve.