What if a spacecraft slowed down on re-entry to just a few miles per hour using rocket boosters like the Mars-sky-crane? Would it negate the need for a heat shield?

—Brian

Is it possible for a spacecraft to control its reentry in such a way that it avoids the atmospheric compression and thus would not require the expensive (and relatively fragile) heat shield on the outside?

—Christopher Mallow

Could a (small) rocket (with payload) be lifted to a high point in the atmosphere where it would only need a small rocket to get to escape velocity?

—Kenny Van de Maele

The answers to these questions all hinge on the same idea. It's an idea I've touched on in other articles, but today I want to focus on it specifically:

The reason it's hard to get to orbit isn't that space is high up.

It's hard to get to orbit because you have to go so fast.

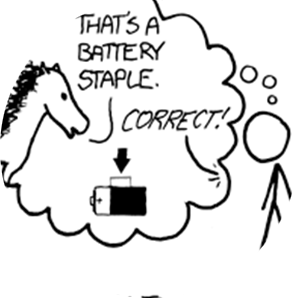

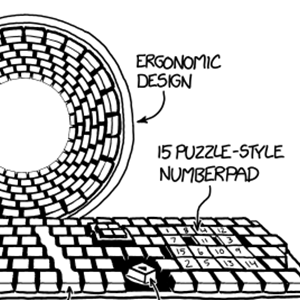

Space isn't like this:

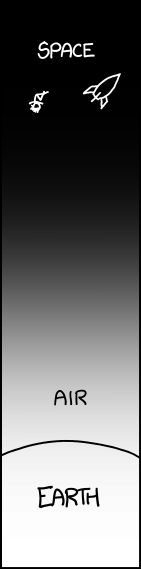

Space is like this:

Space is about 100 kilometers away. That's far away—I wouldn't want to climb a ladder to get there—but it isn't that far away. If you're in Sacramento, Seattle, Canberra, Kolkata, Hyderabad, Phnom Penh, Cairo, Beijing, central Japan, central Sri Lanka, or Portland, space is closer than the sea.

Getting to space[1]Specifically, low Earth orbit, which is where the International Space Station is and where the shuttles could go. is easy. It's not, like, something you could do in your car, but it's not a huge challenge. You could get a person to space with a small sounding rocket the size of a telephone pole. The X-15 aircraft reached space[2]The X-15 reached 100 km on two occasions, both when flown by Joe Walker. just by going fast and then steering up.[3]Make sure to remember to steer up and not down, or you will have a bad time.

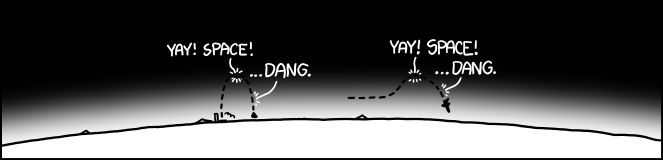

But getting to space is easy. The problem is staying there.

Gravity in low Earth orbit is almost as strong as gravity on the surface. The Space Station hasn't escaped Earth's gravity at all; it's experiencing about 90% the pull that we feel on the surface.

To avoid falling back into the atmosphere, you have to go sideways really, really fast.

The speed you need to stay in orbit is about 8 kilometers per second.[4]It's a little less if you're in the higher region of low Earth orbit. Only a fraction of a rocket's energy is used to lift up out of the atmosphere; the vast majority of it is used to gain orbital (sideways) speed.

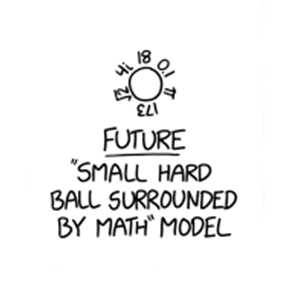

This leads us to the central problem of getting into orbit: Reaching orbital speed takes much more fuel than reaching orbital height. Getting a ship up to 8 km/s takes a lot of booster rockets. Reaching orbital speed is hard enough; reaching to orbital speed while carrying enough fuel to slow back down would be completely impractical.[5]This exponential increase is the central problem of rocketry: The fuel required to increase your speed by one km/s multiplies your weight by about 1.4. To get into orbit, you need to increase your speed to 8 km/s, which means you'll need a lot of fuel: $ 1.4\times1.4\times1.4\times1.4\times1.4\times1.4\times1.4\times1.4\approx 15$ times the original weight of your ship.

Using a rocket to slow down carries the same problem: Every 1 km/s decrease in speed multiplies your starting mass by that same factor of 1.4. If you want to slow all the way down to zero—and drop gently into the atmosphere—the fuel requirements multiply your weight by 15 again.

These outrageous fuel requirements are why every spacecraft entering an atmosphere has braked using a heat shield instead of rockets—slamming into the air is the most practical way to slow down. (And to answer Brian's question, the Curiosity rover was no exception to this; although it used small rockets to hover when it was near the surface, it first used air-braking to shed the majority of its speed.)

How fast is 8 km/s, anyway?

I think the reason for a lot of confusion about these issues is that when astronauts are in orbit, it doesn't seem like they're moving that fast; they look like they're drifting slowly over a blue marble.

But 8 km/s is blisteringly fast. When you look at the sky near sunset, you can sometimes see the ISS go past ... and then, 90 minutes later, see it go past again.[6]There are some good apps and online tools to help you spot the station, along with other neat satellites. My favorite is ISS Detector, but if you Google you can find lots of others. In those 90 minutes, it's circled the entire world.

The ISS moves so quickly that if you fired a rifle bullet from one end of a football field,[7]Either kind. the International Space Station could cross the length of the field before the bullet traveled 10 yards.[8]This type of play is legal in Australian rules football.

Let's imagine what it would look like if you were speed-walking across the Earth's surface at 8 km/s.

To get a better sense of the pace at which you're traveling, let's use the beat of a song to mark the passage of time.[9]Using song beats to help measure the passage of time is a technique also used in CPR training, where the song "Stayin' Alive" is used to . suppose you started playing the 1988 song by The Proclaimers, I'm Gonna Be (500 Miles). That song is about 131.9 beats per minute, so imagine that with every beat of the song, you move forward more than two miles.

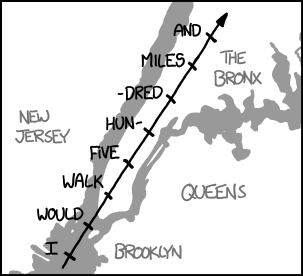

In the time it took to sing the first line of the chorus, you could walk from the Statue of Liberty all the way to the Bronx:

It would take you about two lines of the chorus (16 beats of the song) to cross the English Channel between London and France.

The song's length leads to an odd coincidence. The interval between the start and the end of I'm Gonna Be is 3 minutes and 30 seconds,[10]Based on timing from the official Youtube video and the ISS is moving at 7.66 km/s.

This means that if an astronaut on the ISS listens to I'm Gonna Be, in the time between the first beat of the song and the final lines ...

... they will have traveled just about exactly 1,000 miles.