What would the world be like if the land masses were spread out the same way as now - only rotated by an angle of 90 degrees?

—Socke

It would profoundly alter our biosphere in general and public radio in particular.

Socke asks what would happen if the Earth’s surface were slid around by 90 degrees, putting our current North and South Poles on the equator. We’re not changing the tilt of the Earth’s axis; we’re just imagining that the surface were arranged differently.

We’ll pick the Greenwich meridian for our new equator, putting the new North and South poles in the Indian ocean (0N, 90E) and off the coast of Ecuador (0N, 90W). India, Indonesia, and Ecuador would become polar, while Europe, Antarctica, and Alaska would become tropical.

Where would the deserts and forests be? What areas would get better or worse?

This stuff is complicated. In a moment, we'll start using wild speculation to reshape the face of the planet. But first, a brief story to illustrate just how mind-bogglingly complicated this stuff is:

In Chad, on the southern outskirts of the Sahara, there’s valley called the Bodélé Depression. It was once a lakebed, and the dry dust in the valley floor is full of nutrient-rich matter from the microorganisms that lived there.

From October to March, winds coming in from the east are pinched between two mountain ranges. When the surface winds climb over 20 mph, they start picking up dust from the valley. This dust is blown westward, all the way across Africa, and out over the Atlantic.

That dirt—from one small valley in Chad—supplies over 50% of the nutrient-rich dust that helps fertilize the Amazon rainforest.

At least, according to that one study. But if it's right, it wouldn’t be a crazy anomaly. This kind of complexity is found everywhere. The basic building blocks of our world are crazy.

This is why we can be so certain about large-scale patterns like global warming, where we understand the overall physics pretty well—energy comes in, less energy goes out, so the average temperature rises—but have a harder time predicting how it will affect any particular place or specific species.

So even if I were a climate expert—which I’m definitely not—there’d be no way to answer this question with certainty. There are just too many variables. Instead, think of what follows as a rough sketch of some of the things this alternate Earth could contain.

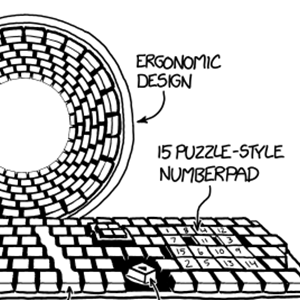

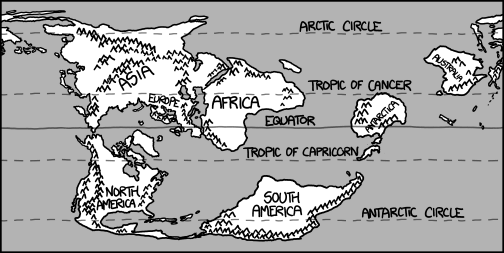

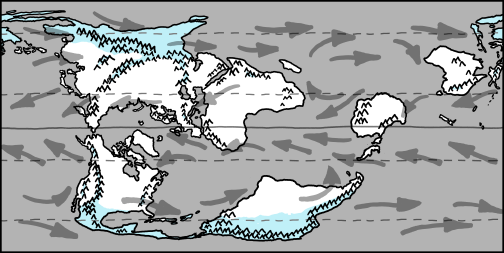

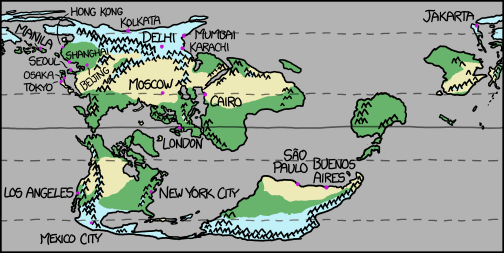

To start, here’s a map of our reshuffled world:

(An equirectangular projection, by the way. This type of equirectangular projection, centered on a north-south meridian instead of the equator, is specifically called a Cassini projection, so a good name for our alternate Earth might be "Cassini".)

Let’s imagine that this alternate Earth develops over millions of years, with ecosystems and climate zones settling out. Then one day we wake up to find our current civilization has been magically transported there—cities and all. What would they find?

The climate on the rotated Earth would depend heavily on the details of ocean and atmospheric heat circulation. We'll guess at some of that, but for now, let's assume this world has extremes which are similar to ours.

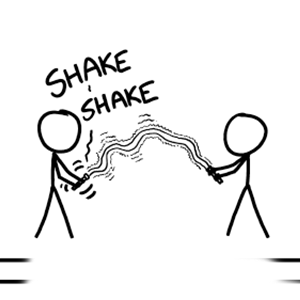

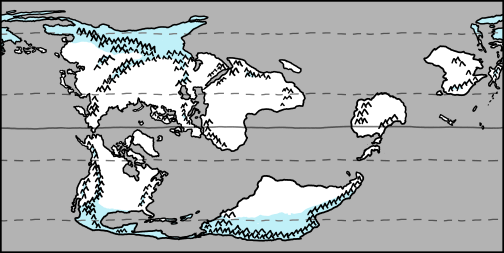

So let's add some ice and permafrost near the poles and in mountainous areas:

Next, we should fill in some green areas and deserts. The locations of these depend heavily on rainfall, so we’ll need to sketch out some winds.

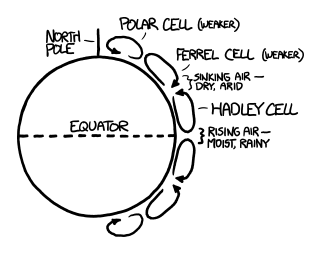

The main driver of our weather is the sun, which heats air near the equator more than at the poles. Hot air rises at the equator and then flows poleward, and cooler air moves in across the surface toward the equator. This circulation is called a Hadley cell.

Hadley cells shift north and south of the Equator with the seasons. At this time of year on our Earth, the sun is directly overhead at about 10°N, which is why hurricanes are forming near that latitude right now.

Because of the Coriolis effect, the surface winds in a Hadley cell flow from east to west. Further north, for most of the temperate zones, the prevailing surface winds are west to east. (At times, there are also east-to-west winds circulating around the poles.)

So let’s fill in some wind patterns—keeping in mind that in reality things would be further complicated by land interactions and the location of persistent high and low pressure systems.

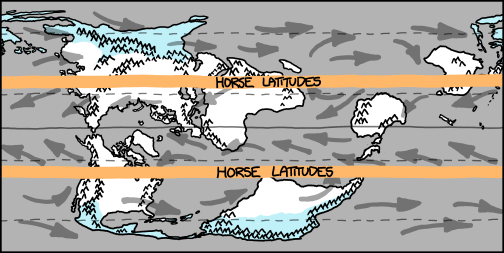

Sinking air is cool and dry, so land under the outer edges of the Hadley cells tends to be arid. These regions, lying a bit poleward of 30 degrees, are known as the horse latitudes.

The rising air at the equator carries moisture from the ocean, which then condenses into rain, so tropical areas are usually wet and thick with growth. Areas near the equator are sometimes dominated by a seasonal monsoon cycle.

In temperate zones, things are more variable. Weather there is dominated by the movement of jet streams and fronts, and depends heavily on geography. Most of the United States is in this type of region.

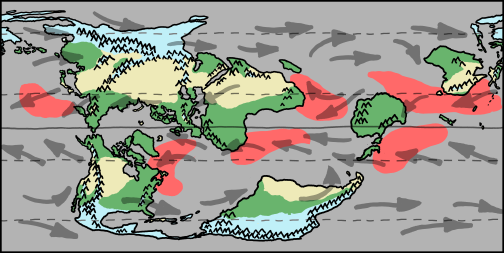

With all that in mind, let’s fill in some arid and lush areas:

(Climates can be hard to predict—for example, in our world, Somalia and French Guiana both sit on the equator, at the eastern coast of a continent, and seem like they should both receive a tropical sea breeze. But coastal French Guiana is dense rain forest while coastal Somalia is an arid desert. The explanation involves the monsoon cycle.)

And just for fun, here’s a wild guess as to where the hurricane basins would be:

Let’s take a closer look at each continent.

North America has a range of climates similar to what it had before, but flipped north-south. The Arctic Canadian provinces are now tropical, while Central America is icy and polar. Hurricanes threaten Greenland, Baffin Island, and the Maritimes. Tropical moisture from Baffin Bay and the northwest (formerly north) Atlantic mixes with cool air flowing down through the US from the Rockies, creating a new Tornado Alley in the prairies inland from Hudson Bay.

South America looks sort of like the old Europe. It's cool and temperate along the Brazilian coast, with boreal forests and grasslands across much of its width. In the south, the boreal vegetation gives way to polar tundra, and eventually to the massive icebound Andes, which cut the continent off from the frozen polar waters. The Amazon, which in our world carries more water than the next seven largest rivers put together, is reduced to something akin to the Mississippi.

Asia is flipped in the same way North America was, with the Siberian coast facing an enclosed tropical sea. The Indian subcontinent and north (formerly southeast) Asia form the new Siberia. The Gobi Desert is no longer in the rain shadow of the Himalayas, but doesn't exactly become tropical.

Europe resembles the old southeast Asia. Great Britain and Ireland look like the Indonesian islands of Sumatra and Borneo. Iceland resembles our Philippines. Central Europe is the new New Guinea, with the Alps the only place on the Equator with permanent glaciers.

Africa is rotated 90 degrees, with south (formerly west) Africa becoming tropical rainforest and north (formerly east) Africa an arid desert. On our Earth, North America is the only continent where tornadoes are common, but in this world, they're frequent in East Africa as well.

Australia is cooler and wetter, with forests across the northern (formerly western) regions.

Antarctica is a clear winner. Without its ice cap, it’s a bit smaller than we remember, but most of it is blanketed with highland rainforest. There are alpine zones around the mountains to the south and west. The researchers at McMurdo and Scott Base on Ross Island wake up to a tropical paradise. If any of them find they miss the frozen wastelands, they can always put in for a transfer to Costa Rica.

Now, let’s see how the world’s largest cities fare:

Some cities get colder.

Mexico City, high in the polar mountains, is buried beneath an ice sheet.

Jakarta is the new Svalbard—a desolate coastal rock too far north even for most Norwegians.

Kolkata and Delhi are icebound, sealed off from the warmer world by the Himalayas.

Hong Kong, Manila, Karachi, and Mumbai are similar to our world’s Anchorage or Reykjavik—the ocean isn’t frozen, but it sure is cold.

A few cities remain perfectly habitable, albeit with some changes:

Seoul, Osaka, Tokyo, Shanghai, and New York City are among the least-affected cities, with climates roughly similar to their previous ones. Shanghai does get colder, but seasonal extremes in all five cities get milder—particularly in Seoul—and substantially wetter.

Cairo is moved slightly south. It’s now surrounded by coastal savannah, with spots of rain forest found around the mouth of the Nile. Though it moves closer to the equator, it doesn’t actually get hotter.

São Paulo and Buenos Aires cool down a bit. They’re now on the northern coast of a South America, which occupies a Canadalike range of latitudes. Their climate is somewhere between that of our New England and that of our Regular England.

Los Angeles is cool and mild. The steady sea breeze carrying moisture up into the San Gabriel mountains makes LA one of the rainiest places in the new US. It closely resembles a wetter version of our Seattle.

And a few cities get much hotter.

Moscow is extremely hot and very dry, with a climate somewhere between our Phoenix and our Baghdad. Russians, who have been surviving in Russia for centuries, shrug with resignation.

London sits in a steamy jungle straddling the equator, with a climate generally resembling Manila's. The food is still bland, the Thames is full of piranha, and it's the only place on Earth where tigers apologize as they attack you.

At the beginning, I mentioned the impact on public radio. To explain, let’s consider one more scenario. Namely, what if this change were made on our Earth, over a fairly short time?

We’re assuming that all the material is magically shifted around, so there are no massive tsunamis or earthquakes. Even so, it would definitely still be a catastrophe. For starters, the ice caps would melt long before new ones could develop, pushing the ocean up by a few hundred feet. The reshuffling of climate zones would come as a huge shock to the biosphere, leading to collapse of the food chain and eventually to mass extinctions at every level.

But if the shift happened just right—and Michael Bay were telling the story—then as the waters of the Gulf of Mexico began to cool and the Mississippi slowed and became an estuary, the region’s wildlife would spread inland.

And one morning, Minnesotans would wake up to the sight of floating rafts of fire ants, followed by five million lost, hungry alligators …

… leading a harrowing, surprisingly bloody “News from Lake Wobegon” segment on what would become the final, fatal broadcast of A Prairie Home Companion.