What if you exploded a nuclear bomb (say, the Tsar Bomba) at the bottom of the Marianas Trench?

—Evin Sellin

Surprisingly little—especially compared to what would happen if you put it just under the surface.

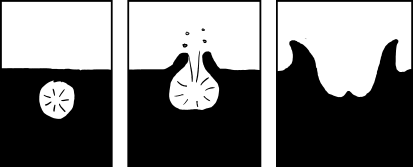

Evin isn’t the first person to think of setting off nuclear weapons underwater. In fact, we’ve actually tried it a bunch of times. This is what it looks like.

Most of the tests, however, involved either small bombs or shallow water. Evin’s scenario concerns neither.

At 53 megatons, the Tsar Bomba was the most powerful nuclear weapon ever detonated, and at 11 kilometers, the Mariana(s) Trench is the deepest part of the ocean. No underwater test has involved bombs anywhere near that size, nor depths anywhere near that deep.

In 1962, physicist Freeman Dyson wrote a memo discussing eight possible novel weapon systems, all of which looked like they’d be possible in the near future, and outlined the potential military uses and dangers of each. This memo has been declassified, but was never published. Freeman’s son, science historian George Dyson, got a paper copy of the memo from his father, and was kind enough to show it to me.

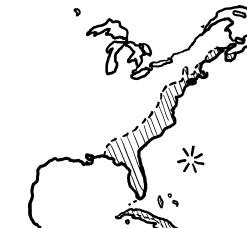

In the memo, one of the eight ideas Freeman discusses is the use of gigaton nuclear weapons as wave generators. It includes this rather terrifying passage describing the detonation of a submerged gigaton mine off the North American coast: “Quantitative study of the destructive effects has not been made. Rough estimates indicate that the inundation would reach to a height of 200-300 feet above sea level, or a distance of 200-300 miles inland, whichever limit is reached first.”

Luckily for the coast, later research paints a less dire picture.

The seminal work in the field of nuclear ocean waves is Water Waves Generated By Underwater Explosions, a sprawling 400-page report produced for the Department of Defense by Bernard Le Mehaute and Shen Wang. The report, published in 1996, exhaustively examines and summarizes all available research about the ocean waves created by nuclear explosions.

The report outlines how when a nuclear weapon goes off underwater, it produces a cavity of hot gasses, which then collapses. If the explosion happens near the surface, it can create some pretty big waves—under some circumstances, they can be hundreds of feet high near ground zero.

Or is it ocean zero?

Fortunately for the coast, these waves are fundamentally different from tsunamis. It turns out that if the waves are very large, they break early, and expend most of their energy creating a narrow surf zone on the continental shelf. This is potentially hazardous to some ships, but much less catastrophic than a direct nuclear attack. When they reached the coast, the waves would be no worse than those from a bad storm.

But those are waves from an explosion close to the surface. A nuke set off deep underwater acts a bit differently.

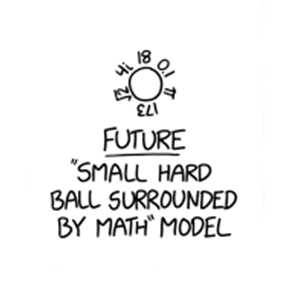

The explosion at the bottom of the Mariana Trench will create a quickly-expanding spherical cavity of hot steam. To figure out how big it gets, we can try a formula from the 1971 paper Evaluation of Various Theoretical Models For Underwater Explosion:

\[\text{Radius} = \left (\frac{3}{4\pi}\right )^\frac{1}{3}\left ( \frac{40 \% \times 53\text{ megatons of TNT}}{\text{Mariana Trench pressure}+\text{1 ATM}} \right)^\frac{1}{3}\approx580\text{ meters}\]

The bubble grows to about a kilometer across in a couple of seconds. The water above bulges up, though only slightly, over a large area. Then the pressure from that six miles of water overhead causes it to collapse. Within a dozen or so seconds, the bubble shrinks to a minimum size, then ‘bounces’ back, expanding outward again.

It goes through three or four cycles of this collapse and expansion before disintegrating into, in the words of the 1996 report, “a mass of turbulent warm water and explosion debris.” According to the report, as a result of such a deep-water closed bubble creation and dissipation, “no wave of any consequence will be generated.”

That “turbulent warm water” is actually quite substantial. The rising column of heat creates a hot spot in the ocean—many degrees warmer than the surrounding water—that lingers for some time.

Earlier this year, Severe Tropical Storm Sanvu passed over the Mariana Trench. The column of deep, hot water from our nuke could conceivably have been enough to strengthen it into a typhoon, much as the deep warm waters of the Gulf of Mexico’s Loop Current sometimes cause hurricanes to rapidly intensify. In addition to the heat energy from the water, Sanvu could whip up a spray containing fallout from the blast, and approach Iwo Jima as a radioactive whirlwind.

Of course, that’s getting a little far-fetched. In the absence of an improbable typhoon interaction, the overall effect of the bomb isn’t quite as dramatic as Evin might have imagined.

... But.

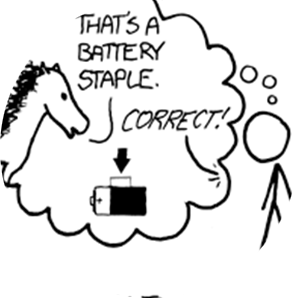

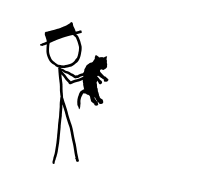

All that changes when this cat enters the equation:

Literally.

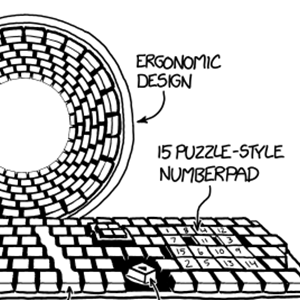

Let’s say that when I’m typing the above equation, the cat hops onto my desk and steps on the “0” key, which inserts six extra zeroes:

\[\text{Radius} = \left (\frac{3}{4\pi}\right) ^\frac{1}{3}\left ( \frac{40 \% \times 53000000\text{ megatons of TNT}}{\text{Mariana Trench pressure}+\text{1 ATM}} \right)^\frac{1}{3}\approx35\text{ miles}\]

If there was enough water, and if the model held up, this blast would expand into a bubble 70 miles across.

In reality, the oceans aren’t that deep. Instead, it blows a hole in the Earth’s crust dozens of miles across, leaving a hole through which briefly glows the magma of the mantle.

Around the early 1990s, scientists started discovering jumbled fields of petrified wood mixed with sand buried beneath the Louisiana and Texas coast. These turned out to be the remains of North American forests swept out to sea by a massive tsunami. The culprit was a comet or asteroid hitting the Yucatan—the impact that killed most of the dinosaurs. The debris played a key role in identifying the 65-million-year-old Chicxulub impact site—this book provides a wonderful account of the unraveling of that mystery.

53,000,000 megatons is approximately the energy of the Chicxulub impact. A blast this size in the Mariana Trench creates kilometer-high waves that engulf the forests of Indonesia, California, and the Pacific Northwest, along with most of coastal China and the rest of the Pacific rim.

Huge volumes of rock and water are blasted into space. The debris takes less than an hour to encircle the Earth. As the chunks of rock fall back into the atmosphere, they heat to a glow—like meteors—igniting global firestorms. The hole fills in, with huge columns of steam and great convulsions.

The Mariana Trench is gone, and with it Guam and the Mariana Islands. The area is now marked by a 100-kilometer-wide scar of magma sizzling beneath the waters of the Pacific.

The majority of the world’s plants die and the food chain collapses completely. Between the famine and the fires, most life on Earth is wiped out.

Stupid cat.