If the Hubble telescope were aimed at the Earth, how detailed would the images be?

—Kyle Rankin

This is a common question. The Hubble operators get it a lot, and their FAQ page answers it. The problem isn’t—as some people say—that the Earth is too bright. As Phil Plait of Bad Astronomy pointed out, Hubble looks at Earth pretty regularly.

The real problem is that Hubble is moving over the surface at over 7 kilometers per second. Even a short exposure would be a blur.

That’s no fun. Is there a way we could make it work? I decided to take a closer look.

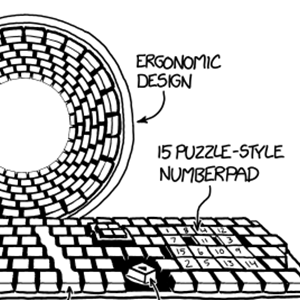

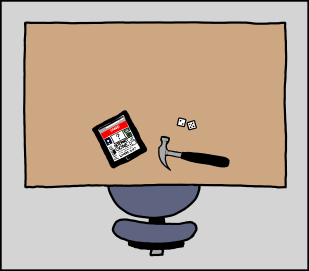

As our picture target, we’ll use this typical desk:

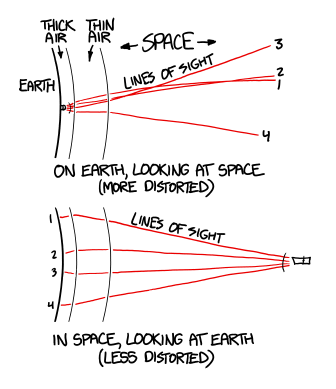

The Earth’s atmosphere won’t be a problem. It’s actually much more of a problem for surface-based telescopes looking at space than for space-based telescopes looking at the surface. The reason for this is geometric:

Hubble is the best visible-light telescope we have, but its resolution does have limits. Pluto, out in the Kuiper belt, lies right at those limits. The best pictures we have of Pluto come from Hubble, but the ex-planet is still little more than a mysterious blur.

At that resolution (about 0.05 arcseconds, give or take) and Hubble’s distance from the desk (about 570 kilometers) the desk would look like this:

But that desk is also zooming by, so even a perfect image will be blurred:

Combining the two effects gives us an end result that looks like this:

That’s no good.

Could we rotate Hubble to track the surface, and eliminate the blur?

Hubble swivels to follow targets. Usually, they’re far enough away that we can assume they’re at infinite distance. The automatic on-board parallax algorithms can’t handle targets closer than about ten times the distance to the Moon. When astronomers want to use it to take pictures of the Moon, sometimes they send it commands to rotate manually, then turn on the camera mid-maneuver.

It doesn’t work very well. Moving Hubble at those speeds is cumbersome with the current guidance package. The resulting photos are better than what you can see with the naked eye, but they’re not very good by Hubble standards. Here’s our desk, with the image degraded by a similar amount that the Moon one was:

Fortunately, the Moon is bright enough that if you’ll settle for a short exposure, you can avoid the problem. This photo was taken with a half-second exposure, short enough that it didn’t have to do much in the way of tracking.

Unfortunately, our desk is moving across the telescope’s field of view about 600 times faster than the Moon. Tracking is unavoidable.

The strange thing is, the desk really isn’t moving all that fast. Hubble is just really slow. To track the surface, it would need to rotate less than a degree per second at maximum.

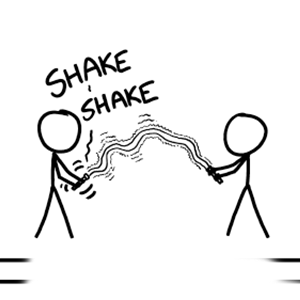

But Hubble wasn’t built for surface tracking. The telescope’s top rotational (“slew”) speed is only a few degrees per minute (about the speed of a minute hand on a clock) and even those speeds are fast enough that its gyroscopes cause it to vibrate, which destroys the image quality.

Clearly, we’d need to disable Hubble’s guidance system and bolt on our own control system. Hubble’s rotational moment of inertia is similar to that of a small carousel; too hard for the existing gyroscopes to move, but not hard in the absolute sense. With our custom control system, it could be made to track the surface, and get photos pretty close to optimal quality:

But this isn’t just a hypothetical situation.

Much of the technology in military spy satellites is believed to be similar to that of Hubble. So in a sense, pointing a Hubble-type telescope at the surface is not only possible—it’s what the US government actually does.