If everybody in the US drove west, could we temporarily halt continental drift?

—Derek

Thanks to plate tectonics, the United States is drifting west at about a centimeter per year. (The people who live there, on the other hand, are on average drifting west at about a centimeter per minute.)

There are 212,309,000 licensed drivers in the US, and since we have more cars than drivers, we can in theory get them all behind the wheel at once. The average car on the road weighs a hair over 4,000 lbs, so we have 850 billion pounds of car (plus around 30 billion pounds of driver) to throw around.

The North American plate, by comparison, is about 25 million square kilometers in area and probably averages around 35 kilometers thick. Given a density of about 2.7 kg/Liter, its mass is probably in the neighborhood of \(2.3 \times 10^{21}\)kg, so it outweighs our fleet by a factor of about six trillion.

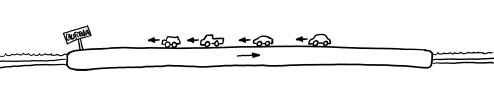

But let's say we give it a shot anyway, and all 212 million of us point our vehicles due west and then floor it. For the dozen or so seconds we’d spend accelerating to freeway speed, our cars would exert very close to a trillion newtons of eastward force on the ground. In the absence of other forces, conservation of momentum tells us it would accelerate the plate up to a blistering 18 cm/year, more than enough to reverse the current motion.

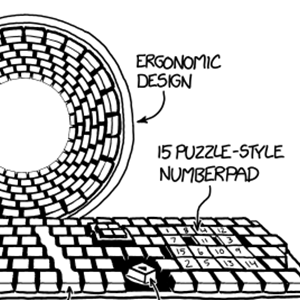

\[\frac{210,000,000 \text{ cars} \times 4100 \frac{\text{lbs}}{\text{car}} \times 75\text{mph}}{2.3 \times 10^{21}\text{kg}} \approx 18 \frac{\text{cm}}{\text{year}} \gg 0.69 \frac{\text{cm}}{\text{year}}\]

But wait. The plates are moving so slowly that their motion isn’t dominated by momentum. They’re held where they are by a balance of forces—the complicated and boring ones from the beginning—and if we’re going to stop them, we probably have to try to figure out what they are. If the plates were drifting along as if they were sliding on ice, then we could push them easily. But it’s possible they’re locked on a slow-but-steady magma conveyer belt, and we can’t move them back without also shifting the flow beneath them.

It was only recently—in the mid-20th century—that we discovered that continents move at all, and we’re still getting a handle on the complex forces between the plates and currents in the mantle that control continental motion. But they sound pretty complicated so let’s try to ignore them. We don’t care how it works—we just want to know if we can break it.

These forces are hard to measure, so we’re not sure how they all work. There’s some evidence that the flow of the mantle along the bottom of the plates isn’t as important as the weight of the edges of the crust as it sinks into the mantle, and the forces in the mantle pushing back against it.

The geology literature gives us some loose estimates to work with. The drag from the mantle, resisting forward motion, is typically in the neighborhood of \(10^5\) to \(10^7\) newtons per square meter, meaning the existing eastward drag force on the North American plate is on the order of \(10^{19}\) newtons.

That’s millions of times more than our fleet. The other forces are greater still. The fact that plates move steadily along in the face of drag that powerful suggests to me that the equilibrium of forces guiding them is probably fairly stable and unlikely to be responsive by our little shove.

But conservation of momentum still works—so something has to move, and that something is the entire Earth, whose rotation would be sped up slightly. If our fleet were centered at around 39º N, the day would be shortened by only about 200 attoseconds—about a trillionth of a percent of the time it took you to read the word “attosecond.” If we drove east instead, the day would be lengthened by a similar amount.

But considering the gasoline required, those 200 attoseconds would cost at least $50 billion. At 100 octillion times minimum wage, that’s a pretty bad hourly rate.

All things considered, it would be a lot easier to just forget to change our clocks next spring and get a whole hour for nothing.